BAD FAIRY: Preface

The Hidden History of the Hookses

He would have you believe that he was born into Carnival People.

He wouldn’t lie about it. It just isn’t quite true.

To the best of Ariel’s knowledge, he was the terminal stop in a storied lineage of grifters, confidence artists, drug dealers, pimps, madams, and a bevy of otherwise enterprising ne’er-do-wells: an unbroken line of malfeasance stretching back to the American Colonial Period.

His ancestors dealt drugs on the Mayflower, or so his mother claimed. At the time of this revelation, Ariel was in fifth grade; Betty was in Year Two of a five-year incarceration at the Elbow Straits Women’s Penitentiary.

She explained the absence of their ancestors Digory and Alfiva from the Mayflower passenger manifest as discretion on their parts.

“Don’t get bamboozled by that whole squeaky-clean Puritan schtick,” she advised Ariel in an entre nous manner. “Total P.R. Added later. It’s how the Puritans got away with the kinky shit they did. People are the same now as they ever were. Believe you me, cocks were floppin’ before the Pilgrims even hoisted sail in Plymouth.” She sighed with the rueful nostalgia of a hippie who missed Woodstock. “Man, that scene was an orgy.”

Catching herself, she tapped the security glass with her prison manicure and stage-whispered into the microphone: “Don’t spill that tidbit to your history teacher. A closed mouth catches no flies.”

The misdeeds of ensuing generations of Hookses brought them distinction as the first and only family to be declared personae-non-grata in all thirteen colonial settlements. Circumstances forced a Westward migration when matriarch Goody Goody Hooks fled their final home in the Massachusetts Bay Colony after weathering a repertory of punishing trials.

“If you’re a prostie worth your salt, holding your breath is a cinch,” Betty explained to her eleven year-old son. “I don’t even mean the attempted drownings. The woman survived a hanging. The Prudy Sues in Salem didn’t know what to do with Goody Goody Hooks.”

The family’s push West eddied for a spell in what would later become the Wyoming Territory, where Leviticus Hooks successfully established a sequel religion to Christianity. The Libidinate Gospel offered a revelatory message – as delivered by a frisky, freshly-resurrected Christ – that denial of the flesh was a Cardinal Sin. Despite a rambunctious start, Leviticus’s burgeoning free-love cult was inexorably upstaged by a rival sequel religion to the southwest. Betty blamed the collapse of the Libidinates on her ancestor’s faulty business model: “Ain’t no joy in sinnin’ when sinnin’ ain’t a sin.”

Cast once more into the diaspora of the American Frontier, the fortunes of the Hooks clan ascended with the California Gold Rush. Prospecting for gold was beneath their station; no self-respecting Hooks would be caught dead panning for fortune amongst the multitudes of grubby, starry-eyed prospectors. Whenever possible, the Hookses made their luck. Their DNA contained a knack for recognizing untapped markets. By the zenith of the Gold Rush, the family operated a baker’s dozen of brothels stretching from Yreka to Calico.

Their enterprises collapsed with the double-whammy of the Civil War and the discovery of the Comstock Lode, which sent their lusty clientele on an eastward stampede. Though the Hookses were abolitionists at heart, military service for the Union was out of the question. They became provisioners to the Confederacy instead, undermining their military efforts with deliveries of weevil-infested grain, tainted beef, and uniforms fashioned from glue, scabies and lint that melted in a gentle rain. Though their efforts went unrecognized by history, the Hookses privately took credit for the Union’s eventual triumph.

Reconstruction found the Hookses setting down roots at last. Family matriarch Dolorosa Hooks drew from the spoils of Confederate misery to purchase a sprawling three-story 1836 Creole Townhouse in the Fauborg Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans.

Dolorosa opened the Cozy Rooms as a modest, efficient brothel whose survival depended on regular, hushed payouts to select city officials – whose indiscretions Dolorosa carefully journaled lest they renege on their quiet bargain. In 1897, city alderman Sidney Story passed an ordinance creating “The District,” an eighteen-block area in Fauborg Tremé, designed to corral the free-range licentiousness that riddled post-Reconstruction New Orleans. Story garnered unintended fame when the nickname “Storyville” supplanted “The District” among locals.

As luck would have it, the Cozy Rooms was perched just within Storyville’s perimeter at Basin and Iberville. In her declining years, Dolorosa bequeathed the Cozy Rooms to Mercy, her mannish, practical daughter (and grandmother to Betty).

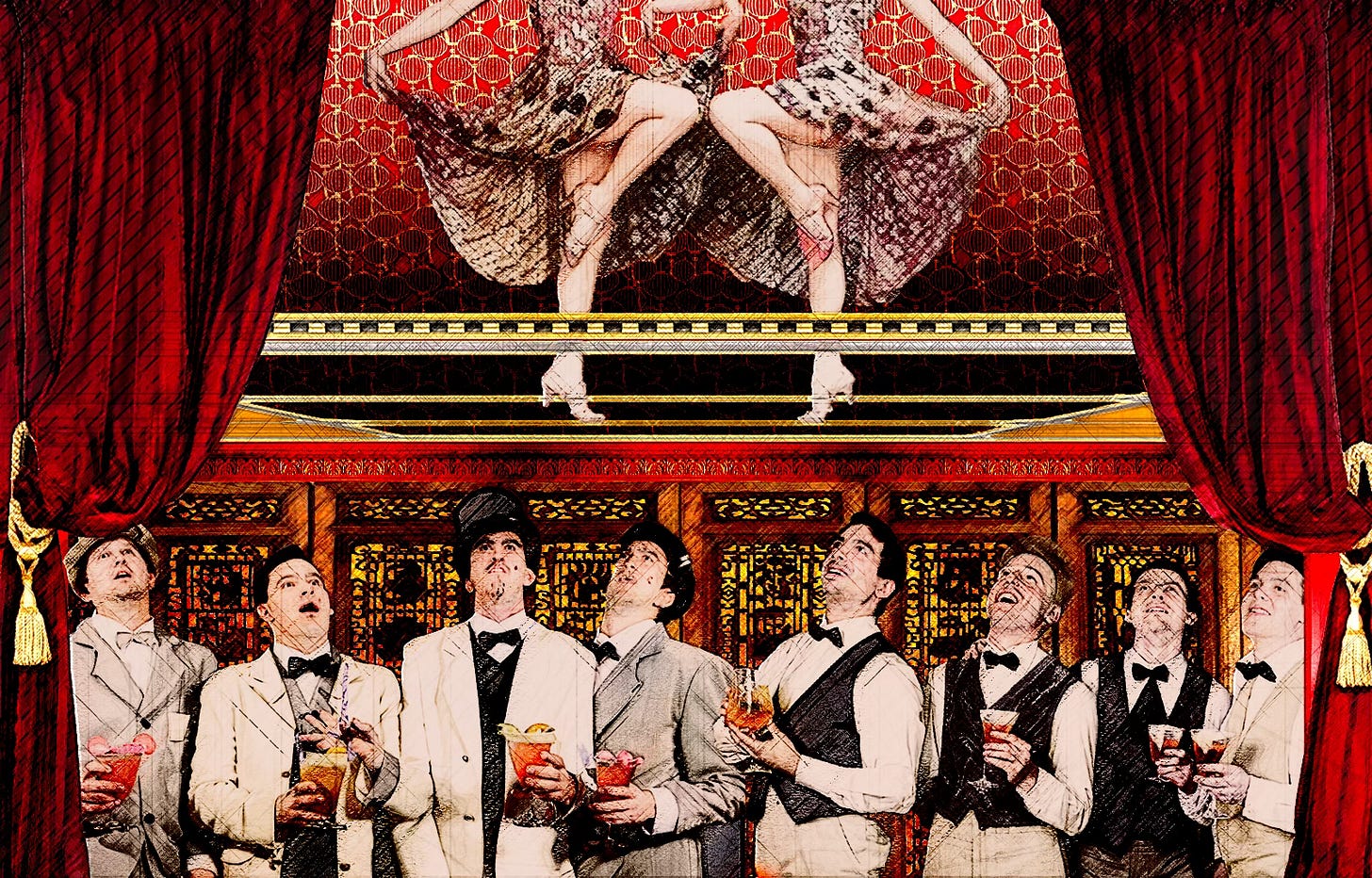

As competition sprung up on all sides, Mercy promptly commenced renovations to the Cozy Rooms. She spearheaded numerous structural adjustments with the aid of her Sapphic girlfriends but was stymied by matters of decor. Cheerfully confessing her lack of elan, Mercy enlisted Dick and Dick, a mincing pair of rakish inverts, to polish the bland whorehouse into a gaudy, gilded confection that she proudly advertised in the notorious Blue Book guides:

As with many among the Hooks lineage, Mercy was incongruously named. Her cultured, gracious public persona was deliberate affectation; in private, she wore trousers, took snuff and was rumored to have shot two rabble-rousers dead in the parlor. But true to her name, Mercy kept a maternal, protective eye on the two dozen-odd ladies in her employ – as well as the handful of young male squires whose services, while unadvertised, were famous amongst the homosexual underground.

1908 found Mercy on the edge of menopause, bemoaning the absence of an inheritor to continue the vaunted family name. She decided to bear a child before biology kiboshed the option, but shuddered to imagine coitus with a heterosexual man (a human category that she privately abhorred). So Mercy again enlisted Dick and Dick for assistance. The threesome kept mum about the goings-on in Mercy’s bedchamber that night, but the girls (with ears pressed to the door) reported hours of shrieking laughter, abetted by bottomless gin and an opium pipe.

It worked. Nine months later, Betty’s grandmother Hope was born, soon to become the darling of the neighborhood. None could ascertain which Dick was the father, as Hope bore characteristics of both: she had one Dick’s sticking-out ears, and the other Dick’s aggressive cowlick.

America’s ascent into world war brought a temperate chill to freewheeling Storyville. Concern for the moral fiber of Navy recruits led to its decommissioning as a legal red-light district in 1917, despite the impassioned protests of New Orleans Parish officials. Rumors abounded that Storyville’s eighteen blocks were destined for the wrecking ball, to be replaced with public housing.

In retort, Mercy had the three-story structure of her beloved Cozy Rooms sawed into thirds, jackscrewed up from the foundation, and reassembled in a lot just north of the French Quarter at 1101 St. Monica Street.

Business steadily resumed in the new location as law enforcement looked the other way, palms greased by no small percentage of Mercy’s earnings. Money abounded nonetheless; the advent of Prohibition proved a godsend as customers flooded through the side door to enjoy Mercy’s bathtub gin alongside the scorching jazz that filled the courtyard every night.

But 1929 brought misfortune beyond the cratering stock market. In December, a quartet of bandits invaded the Cozy Rooms during the midafternoon lull, beckoned by rumors of treasure-filled safes hidden in Mercy’s boudoir. Concerned as always for the safety of her girls, Mercy brandished a sawed-off shotgun in the courtyard only to be cut down by retaliatory gunfire. In under a minute, Storyville’s madam of legend bled out on the cobblestones.

The invaders fled, empty-handed. Nobody benefitted from the incident and the brigands were never captured. Distraught with grief, daughter Hope closed the doors of the Cozy Rooms. The prostitutes dispersed one by one, clutching a gift that Hope credited to her mother: a purse filled with means enough to begin a new life.

The place was haunted now, drafty and silent. Hope lacked the heart to sell it but had no desire to remain. On a drunken, reckless night in February 1930, a milquetoast tourist from Florida proposed marriage to Hope at a Bourbon Street speakeasy; to Gary’s astonishment, she took his hand. A Parish clerk oversaw their wedding the following day. When matters of business called Gary back to Panacea on Florida’s Apalachee Bay, Hope promised to join him after finishing business of her own: securing the only home she ever knew.

Hope spent lavishly on the Cozy Rooms in those final weeks. She had the roof replaced, the windows repointed, the hatches battened to withstand the most Apocalyptic weather that God could devise. Once the workmen cleared their tools, Hope exited the grand front entrance without a backward glance. She slapped a heavy padlock on the doors, climbed into her Cadillac V-16, and traced the northern Gulf of Mexico 500-odd miles eastward into the arms of her doting husband.

1101 St. Monica Street stood vacant for a quarter century.

In 1955, Hope’s enterprising daughter Magdalene reopened the Cozy Rooms as a rooming-house for bachelors, setting aside a couple of apartments for family use. Her daughter Betty spent the happiest summers of her childhood playing in its halls.

By the Seventies, the building was crumbling into ruin, more flophouse than the rooming-house once advertised. Upkeep became more trouble than it was worth; there seemed to be no building code that the Cozy Rooms did not transgress.

In 1974, the year of Ariel’s birth, Magdalene shut the building’s doors once more. Though tempted to sell the place, she kept the promise that she swore to Hope on her deathbed several years prior: that the Cozy Rooms would forever stay with the Hookses.

And over the twenty-eight years that followed, not a soul entered the Cozy Rooms until Ariel broke the lock.

###